32. Thomas Shapter 1849

During the three

years 1832-34 over 400 Exeter and St. Thomas residents lost their lives in

outbreaks of Cholera. 1832 was especially severe

with over 1,100 cases reported and some 345 deaths between July 19th and

October 27th in Exeter. In 1849 Thomas Shapter MD (elected to the chamber in

1833) wrote a report describing the cholera epidemics affecting Exeter in his The

History of the Cholera in Exeter in 1832 (published in London by John Churchill and in Exeter by Adam Holden,

1849). The disease showed that the population of the city was still distributed

in the same pattern. The well-to-do parishes were those about the High Street,

above North & South Streets, St. Martin, St. Petrock, St. Stephen, St. Lawrence,

All Hallows and the Bedford area. The poorer parishes were St. Edmund, St. Mary

Major, St. Mary Steps and probably All Hallow on the Walls, in effect the

western part[1]. Many of the great merchant houses had been converted into

tenements with 8 to 10 persons sharing one room and some larger properties,

still occupied by tradesmen and professionals, were now in the midst of

brutalising slums.

In the last part of the 18th

century the prosperous families escaped from the city to Dix’s Field and the

Barnfield or even further out to Heavitree. By the turn of the century Exeter

had changed. The thriving industrial and commercial city of 1700 was now a

supply centre for goods and services. The cloth industry had all but

disappeared. This was all reflected in the Chamber where the members

represented the professions and gentility and no longer the merchants and the

guilds. The city as Newton wrote in the census of 1831 defined the problems and

Exeter, relapsing into the status of a large market town, was ill fitted to

deal with them.

Following the cholera epidemic the worst slums were pulled down and some 13 miles of sewers were laid. Plans were made to build 200 labourer’s cottages and although they failed, they led to the Newtown building which started in 1839. In 1838 the commissioners raised £3,000 for the paving of the streets, partly for vehicles and pedestrians and partly to remove the open sewers. In 1834 the New North Road (from Belmont to the New London Inn) was completed and in 1836 Fore Street was lowered to improve the slope. In 1838 Magdalen Street was widened with the houses by the White Hart set back and projections removed and in 1839 the new Queen Street was built between Maddox Row and the High Street. By 1840 the new street pattern was in place to remain within the city for the rest of the century.

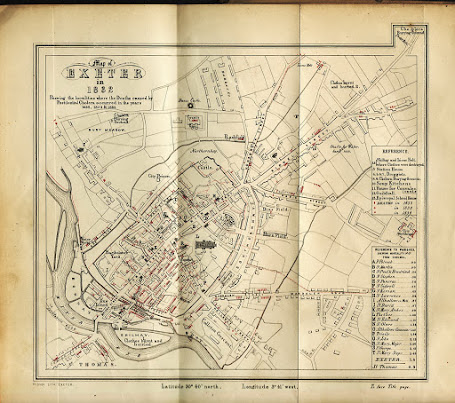

Title: Map of EXETER in 1832 Showing the localities where the Deaths caused by Pestilential Cholera

occurred in the years 1832, 1833 & 1834.

Size:

177 x 205 mm (slight projection top right) but no scale. Latitude 50o40’ north and Longitude 3o41’

west

are, however, noted.

Imprint: Risdon Lith: Exeter. Note: To face Title page.

The area shown is from St.

Thomas, bottom left, to Pester Lane, top right, where

the border is broken to include the cholera burial ground which gave it its

name. There are two references: above for references to the cholera such as

soup kitchens and deaths in the

three years; below for parishes and mortality rates. Interesting points are the

shafts for water sunk off Sidwell Street in 1832; Long Brook runs alongside Exe

Lane; and the new roads are not shown.

It is a sad drawing showing the

places of burial and where clothes burning took place. Death rates were

especially high between South Street and Shilhay with very high numbers in the

area of Ewings Lane. The final irony: the Great

Shilhay, site of the woollen industry for so many years is now the place where

the clothes were burnt and buried.

[1] St

Mary Major had 388 inhabited houses but only 30% were rated and in St. Mary

Steps only some 17% were rated: whereas 80% were rated in St. Lawrence and 100% in St. Martin.

No comments:

Post a Comment