A Brief History of Exeter by Dick Passmore

A

Brief History of Exeter

Early occupation

The

Anglo-Saxons occupied

Exeter during the 7th century and an Abbey was built, approximately on the site

of the existing Cathedral. Then followed the Danes, who took the city in 876,

but were dismissed from Exeter by King Alfred only to return

about one hundred and fifty years later! They were at first repelled, but, led

by King Sweyn, later gained

access to the city and plundered it, setting buildings alight and destroying

the Abbey. They left the city in virtual ruin, and never returned. The Normans took over

England in 1066, and shortly afterwards found Exeter, already a busy town, with

almost five hundred houses and a population of some 2,500. The occupation of

Exeter by the Normans saw the rebuilding of the Abbey – probably one of the

highlights of Exeter’s history, for it was the Normans who started to create

what is now the magnificent Cathedral of St. Peter, set in the

centre of the city. The twin towers of today’s Cathedral are indeed of Norman

origin.

The

Castle

George Oliver in The History of the City of Exeter devoted

a chapter to the origins of the castle and walls which he attributed to King

Athelstan at some time

between 925 and 941 giving the outline traced by Kerslake (see 46). Despite

extensive destruction by Sweyn, as mentioned above, the city rose again under

the support of Canute and Edward the

Confessor so that by the

time of the conquest Exeter had gained city proportions. However, the castle is

not documented in the Domesday Survey of 1086 and was

possibly only completed some time later. The gateway certainly leads one to

suspect completion during, or shortly after, Norman architectural influence.

John

Leland is reputed to

have visited Exeter in 1542 on his extensive travels and a manuscript plan of

the castle dating back to the 16th century is extant (35). However, although

long credited to Leland himself, the manuscript plan in the British Library may

be a later speculation of what Leland saw, produced some years after his death (in

1552).

Norden (36), who surveyed the castle in 1617, gives us the most detailed description of the castle. He shows the sally port in the extreme North East corner, and a tower between the entrance gate and the South East corner, but omits the bastion clearly shown by others (e.g. manuscript maps of 1600 or the manuscript maps of Hooker) between the entrance gate and the north west (i.e. Athelstan’s) tower. However, the castle shown on one of Hooker’s drawings of St. Sidwell’s fee (see 61) clearly shows both the bastion and Norden’s tower. However it is safe to assume that at some time both existed. The plan in Jenkins’ History of Exeter in 1806 (18), based on the so-called Leland plan, moves the sally port back towards the sessions house in the centre and shows both bastions (but not the tower between the gate and the south east corner). In an article in 1912 C B Lyster, writing about the city walls (Devon & Cornwall, Notes & Queries Vol. VII), noted that there were archaeological finds that showed the foundations of both. One is left with the supposition that the south bastion was so ruined by the beginning of the seventeenth century that Norden did not consider it worth drawing.

Parishes

Frederic Kelly’s

Directory of Devonshire (e.g.

1893, p.171) mentions that in 1222, Exeter had 19 churches, two of which (St.

Sidwell’s and St. David’s) "stood without the walls”. White’s Directory of Devonshire for

1850 states that prior to 1658 Exeter had 32 churches (probably including the

suburbs and non-conformists), although 12 had been sold in that year (p.81).

The same directory states that in 1850 the city and suburbs had no less than 21

parish churches and several episcopal chapels. It was during the thirteenth

century that parishes first appeared in Exeter, although there had been many

churches constructed during earlier centuries, none had defined areas, or

parishes as we now know

them. The newly created parishes tended to follow the lines of streets and

lanes, and people resident within those areas would attend the church within

that parish, each parish having its own priest. Although some of the parishes

disappeared long ago, early maps of Exeter show the names of parishes within

the city. It was not until 1956 that parish boundaries were revised, some being

amalgamated with adjoining parishes, with priests looking after the spiritual

needs of two, three or perhaps four parishes. That system still exists today.

View of the High Street in Wheaton's Hand-Book of Exeter, 1846.

A famous visitor to remark on Exeter’s wealth and success was Daniel Defoe. In the early 1700s he remarked that Exeter

was full of gentry and good company, and

yet full of trade and manufacturers also. Apparently it was said in those

days that few places could boast both of these “virtues”.

It was at this period that Exeter’s woollen and cloth trade started to

prosper. Mention has already been made

of grist mills, but there were a considerable number of woollen mills in the

area as well, located alongside the river. Later there were also paper mills,

but the woollen mills were, perhaps, of far more significance in the early

days.

It was at this period that Exeter’s woollen and cloth trade started to

prosper. Mention has already been made

of grist mills, but there were a considerable number of woollen mills in the

area as well, located alongside the river. Later there were also paper mills,

but the woollen mills were, perhaps, of far more significance in the early

days.

The various mills in the city produced cloth in huge amounts, and this was sold

all over the country. Few of these mills are shown on maps. The Fulling Mill at

Blackaller Wear is shown on one or two maps and is clearly visible on Tozer’s

map (15), but others are either not shown or are indiscernible. Later, during

the 1600s, serge became more popular as it was far more hard-wearing, and most

mills turned to that material to enhance their trade – hence Celia Fiennes’

comments noted earlier. Local cloth merchants became extremely wealthy and

constructed their out-of-town houses in the suburbs of the city, many of which

still exist, although few now remain as private residences, many having been

converted into apartments and others used for corporate reasons. One should

note the extensive rack-fields - a sign of the extensive fullers’ trade. The

extent of the industry is shown on various maps by the extent of the

rack-fields: two rows in 1587 (1), five fields in 1709 (8), seven fields in

1792 (15), five in 1805 (16) and none by 1845 (31).[1] Rack Lane, close to the

West gate, is named after the numerous drying racks located in that

street.

Growth

of the city

During the

thirteenth and fourteenth centuries Exeter started to grow, and records show

various taverns, houses, shops and other buildings springing up, making the

city a busy place in which to live and work. Taverns, it has to be said, were

of considerable importance in those days. Not only were they ale-houses – and

thus of social importance, they were also meeting places, and places of

entertainment. They were also a useful means of providing an address; when

Hermann Moll’s Fifty-Six New and Acurate Maps was

published in 1708 it was printed by John Nicholson at the

Kings-Arms, John Sprint at the Bell in

Little-Britain and Andrew Bell at the

Cross-Keys and Bible in London, for example. In Exeter the Seven Stars inn also

served as one of the city’s earliest theatres, and is thought to have hosted

John Gay’s The

Beggars Opera in 1728 as the first performance outside London. The city

was filling up within the old walls, and space was becoming valuable.

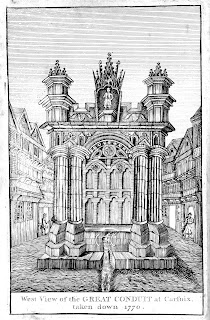

The end of the

12th century also saw one of the most important additions to Exeter – the

underground water supply. Until then,

citizens would collect their own water from the Exe, or pay water-bearers who

would carry pails of water on yokes throughout the city, selling the water from

the River Exe to houses and businesses. The introduction of piped water was of

significant importance to the city, although Minchinton (1987) states that

water bearers were still existent in the early 19th century. The underground

system commenced with the tapping of a spring in the higher part of the parish

of St. Sidwell, owned by the Dean and Chapter. They were the first to take

advantage of the new system, and were able to supply the Cathedral with fresh

water. The water was brought underground into the Cathedral Close where it

terminated in the newly-built St. Peter’s Conduit. A further supply was taken

to Fore Street, to serve St. Nicholas’ Priory. However, more importantly, in

1346 an agreement was made whereby the water from St. Peter’s Conduit could be

taken to another new conduit in South Street. This was later demolished and in

1441 the new Great Conduit was constructed at The Carfax - the junction of High

Street, Fore Street, South Street and North Street. The conduit stood until the

late eighteenth century, having supplied Exeter with water for over three

hundred years. The Great Conduit can clearly be seen on various maps, including

those of Hooker (1), Speed (2), Braun & Hogenberg (3) and Izacke (7) and is

reference 6 on Nicholls’ plan (page 12). Today, Exeter’s “underground passages”, as they are

now named, are in fact the narrow, low tunnels constructed to carry water from

St. Sidwell’s, open to the public where visitors can see a small section of the

original passages and pipework. It must be said, however, that they are not

suitable for those who suffer from claustrophobia.

From the Roman

days, when it was a walled city, Exeter and its population have both grown

century by century, until Exeter is now a city of some 125,000 people, taking

up an area of several square miles. Being walled, the city was somewhat insular

(as were many other cities and towns), and although the walls were designed to

protect the city, on more than one occasion those walls have been breached and

the city invaded – notably by the Danes c.876, and William the Conqueror in 1068. In

1496 Perkin Warbeck attempted to

take the city, but was repelled. Henry VII visited the city shortly afterwards

and presented it with a Sword and Cap of Maintenance as a gift, in

gratitude for the city’s loyalty to the Crown. Both the Sword and Cap are

retained to this day as part of the city’s Regalia. In 1549 Hooker witnessed the

siege during the Prayer Book Rebellion. During the

English Civil War, Exeter was

besieged and taken over by the Royalists in 1643 only to be surrendered to

General Fairfax in 1646. Since

then the city has been free of any form of siege, although it was, of course,

seriously affected by German bombing raids in 1942, as will be seen later.

Exeter documented

Exeter

has been inhabited for over two thousand years, and the main thoroughfare, High

Street, has been in continuous use during that period, and was originally one

of several ridgeways around the city. The story of Exeter is therefore of great

interest to historians, and has been documented since at least the 15th century

(and possibly earlier), by way of manuscripts, books and maps. Certainly John

Hooker’s numerous writings such as his Catalogue

of Bishops in

1584 and his other works, many only extant as manuscripts, of around that time

are amongst the earliest and provide us with a good perspective on life in

Exeter at that time. Almost a century later Richard Izacke wrote his Antiquities of the City of Exeter - a

book now sought by collectors - and which provides the modern reader with a

catalogue of events, both major and trivial, but which nonetheless give us a

vivid impression of life at that time. His son’s continuation is also a

valuable contribution to Exeter’s historical writings.

While

later writers tried to imagine what Exeter looked like before the Middle Ages

(e.g. Kerslake or Freeman) the earliest contemporary maps of Exeter, for

example Hooker’s map of 1587 (1), depict the walled city on the north bank of

the River Exe, with just a few outlying settlements, and those being mainly

agricultural. Hooker’s is the first printed map of the city and, as such, shows

not only what it was like in 1587 but probably what it had been like for the

previous three or four hundred years and, to some extent, how it would remain

until the end of the 18th century. The south east quarter, East Gate to South

Gate, including the Cathedral was inhabited by the well-to-do, with both sides

of the High Street and Southgate Street a mixture of shops and merchant’s

houses. The rest of the city was populated by the poorer artisans and workers,

becoming poorer towards and beyond the walls. Yet, as Hooker drew it, the city

was full of courts, gardens and even small fields; such industry as there was

is mostly confined to the south west slope down to and beyond the West Gate

where the whole cloth trade was situated.

But

Hooker was to some extent misleading - it was difficult to show that the west

end of High Street was narrow and

steep, for example. The principal road to the West Gate and thence to

the bridge was through the Shambles, Butcher’s Row

and down

Smythen Street; too steep for

wheeled traffic, it was only suitable for the pack-horse and the pedestrian

brave enough to climb beside the open-drain and it would remain in this state

until the 19th century. Hooker shows clearly, however, that there was little

development beyond the walls except close to the four main gates and the Water

Gate leading down to The Quay.

The maps from the 17th and early 18th centuries

are interesting as they all differ slightly in some respects, but all retain

the basic layout of the city and its more prominent buildings. Many include the

names of such buildings and also the names of churches, and some will include names

of areas and large houses outside the city walls. Good examples are the maps in

Richard Izacke’s history of

Exeter and the map included in his son’s continuation. The former (7) depicts

Exeter in the third quarter of the seventeenth century, while the latter (with

Sutton Nicholls plan, 9

illustrated over) presents Exeter in the first quarter of the eighteenth

century. However, later maps, such as that of Tozer in 1792, give

a much more detailed image of the area within and without the walls (see 15).

During the 17th

and 18th centuries, various authors produced their versions of the city’s

history, and during the early 19th century several more histories were

produced, including those of Jenkins (17), Oliver (with an early

view of the castle precincts, 35), Freeman (53) and Thomas

Brice (1802) etc. Most included a map of the city. Printing processes were

being developed year by year, and as books and maps became easier to produce in

numbers, so they became more readily available to the public in shops, reading

rooms and other similar institutions. As will be seen in the following pages,

the mapping of Exeter has been considerable over centuries, and in themselves

the maps tell a large part of the city’s history.

Andrew Brice, mentioned above, was one of the first people to produce an Exeter newspaper. His first enterprise was The Postmaster, subtitled The Loyal Mercury. He went on to produce several journals, including The Weekly Journal, or the Old Exeter Journal as it was also known. After the death of Brice the paper continued being produced by his partner, Barnabas Thorn, and subsequently by Thorn’s son until it was purchased by Robert Trewman who renamed it The Flying Post.

Exeter’s national importance

A

few centuries ago, Exeter held a proud place in England. It was one of the more

important areas for trade, and one of the oldest places in the country.

Certainly, in earlier days, Exeter was one of the three most important cities

in England. The reasons for this importance are quite simple. Firstly, early

Exeter was suitably located on a plateau approximately one hundred feet above

the River Exe. The ground

around the city was most suitable for excavating building materials - bearing

in mind that early buildings in the area were constructed of timber and ‘cob’,

the latter being a mixture of mud, straw and even dung, which, when mixed

together and dried out, formed a suitable material to construct walls. The

river Exe was easily accessible for

a good supply of fresh water,

and, in those days, fish in abundance. The area surrounding the city was

eminently suitable for agricultural use, the soil being rich and fertile.

Hundreds of acres of farmland around Exeter were able to grow large areas of

corn and other crops, whilst the fertile meadows allowed cattle and sheep to

graze freely. Thus Exeter had a continual supply of fish, meat, and crops, with

many grist mills supplying sufficient amounts of flour for making bread. It

was, as were most towns and cities of that era, “self sufficient” in most

respects.

Transport

in earlier centuries presented merchants with a problem, for their wares needed

to be distributed far and wide, even abroad. Horse traffic was slow, and

railways did not come into being until the early nineteenth century, with motorised vehicles arriving much later

still. Exeter, however, had the advantage of being close to the English

Channel, with a river running alongside the city. Over the years, Exeter

developed into a port of great importance, and in those days, boats could sail

from the English Channel, up the estuary of the River Exe, and dock alongside the

quay in Exeter to load and offload goods. Various buildings still stand adjacent

to the quay relating to the work carried out there. A few yards away from the

docking area is the Custom House, a magnificent

building dating from 1681, and said to be the first commercial building in

Exeter constructed of brick. It was from here that all revenues were collected

– all goods being weighed on the King’s Beam that is still

in existence a few yards from the Custom House. Nearby is the Wharfinger’s

House, where lived

the “manager” of the wharf, or quayside. Also nearby is Cricklepit Mill, once a

fulling mill but later converted to a corn mill and also used for a time as a

saw mill. The mill has, in the past few years, been totally restored and is now

in complete working order – a popular tourist attraction.

The

undeniable fact of Exeter’s prominence in trading by shipping was not

appreciated by the Countess Isabella de Fortibus, a member of

Devon’s Courtenay family. In the 13th century, she decided to construct a weir

across the river to prevent large ships going to the port of Exeter. There was,

in her mind, solid reasoning in her decision and action.

The

Courtenay family were the Earls of Devon, living at Powderham Castle – as indeed

they still do. They owned huge tracts of land surrounding the city, including

the smaller port of Topsham, a short distance up the estuary from the English

Channel. The Countess realised that the family were losing a lot of trade to

Exeter, and needed to make more use of the port of Topsham. By preventing shipping heading onwards to Exeter, ships would be forced to

offload at Topsham, the nearest port to Exeter, thus providing additional

income for the family by way of tolls and fees on the cargoes offloaded at

their port. Exeter would be deprived of these fees by the weir being

constructed. In 1284 the weir was created, with a small central gap of less than thirty

feet, thus allowing only smaller boats to continue up river. The larger sailing

ships were now forced to dock at Topsham, paying their dues to the Courtenay

family, and then having the added expense of requiring their goods to be

transported to Exeter by horse and cart. The area close to that weir is now

known as Countess Wear, or sometimes

more correctly referred to as Countess Weir, as it perhaps should be known.

Exeter’s

wool and cloth industries

Probably the

most important factor that made Exeter a place of considerable wealth and

importance was the cloth and woollen trades of the 16th, 17th and 18th

centuries. In 1698 Celia Fiennes visited Exeter

and gave a glowing report of what she saw and found here.

Cathedral Yard from Thomas Moore's History of Devon, 1829

A large amount

of the combed wool was sent out to the cottage industries of country spinners

and weavers who returned it later to market as woven serges. Other towns such

as Tiverton carried out the earliest processes but again returning the serge to

Exeter. The raw wool was brought in, sorted, spun, combed and woven. The

dampened fabrics were then beaten in the fulling-mills, a process in Devon

called tucking. The fulled material was then

taken to be stretched and dried in the rack fields. When dry it was teased to

raise the nap and then sheared for a smooth finish. Finally it went to the

drawer to repair blemishes and to the hot pressman. If colour was required this

was now done but only to commission. All of this work with the trading and the

packing was carried out in the south-west part of the city and down on Exe

Island and Shilhay.

Daniel Defoe claimed that

Exeter’s weekly serge market was second only in size to the Brigg Market at

Leeds, in Yorkshire, the largest in England at that time. He further maintained

that the Devon woollen industry was the

most important branch of the woollen manufacture in the whole of England.

Exeter was certainly recognised as being of considerable importance within the

woollen trade, and also in other trades.

Throughout the 18th century Exeter’s wool trade slowly decreased due to the considerable number of mills being built in the north of England, and also the impact on trade caused by the European wars. In the middle of the 18th century Exeter’s wool trade was only half the size it had been at the beginning of the century. By the end of the 1700s it had virtually died in the city although some woollen and serge racks can still be seen in the maps of Hayman (16, 17 and 20). It is interesting to note that the only surviving Trade Guild in Exeter is that of the woollen trade – The Incorporation of Weavers, Fullers and Shearmen, who still meet at their own Guild hall – Tuckers Hall – in Exeter’s Fore Street. This guild hall must not be confused with the magnificent Guildhall in High Street – one of Exeter’s oldest buildings still in daily use, mainly for civic functions, although exhibitions and various meetings are frequently held there. The ancient Tuckers Hall, still overseen by a Beadle, is one of Exeter’s finest buildings, containing many relics of the trade.

Exeter toll houses and turnpikes

During the 18th

century, roads were being improved largely due to the Turnpike Trusts. Thus travel

became easier and quicker, and contact between cities and towns increased, as

did trade. Early tracks and roads connecting towns and villages were not

‘owned’, and were therefore not maintained. With the advent of the Turnpike

Trusts, this altered, and roads became an important part of life, not just for

businesses, but also for the public. From the fourteenth century, the idea of

levying tolls to upkeep roads was in place, but Turnpike roads came into being

in the mid seventeenth century. Turnpike Trusts were regulated by Parliament,

but the day-to-day running was left to local worthies or councils, who formed a

“trust”. They were responsible for sections of road, and subsequently charged

for the upkeep of them. The system did not reach Devon until the 1750s, and

Exeter in 1753. There then began the appearance of turnpikes and toll-gates, with suitable

toll-houses alongside. Various charges were set, and tolls were levied

according to usage. For example, a person on horseback may be charged one

penny, a farmer with a small flock of sheep ten pence, and a carriage with six

horses one shilling – but of course ten pence today is vastly different from

the 1800s! Exeter had many toll-gates, none of which survive, and only one or two of the former toll

houses remain in the area, such as those in Topsham Road and New North Road.

The toll system continued until the advent of the railway in England in the

early 1800s, but by the end of the 19th century it had virtually ceased. The

railway became an easier means of transport for both passengers and goods. Today, of course, the idea

of levying tolls is commonplace on roads and bridges in many countries.

Exeter

in the 19th century

So

we move on to the nineteenth century, and see an improvement in the city,

although the French Wars during the

latter part of the 18th century had prevented much of the city’s exports going

to Europe. Exeter at the beginning of the nineteenth century had around 20,000

citizens. Various areas were literally taken over by the considerable number of

wealthy merchants who still survived, despite the Wars. Pennsylvania, for

example, was popular for its magnificent views across the city, and several

large houses were constructed there, including the splendid properties of

Pennsylvania Park. Other areas

were to follow the pattern, and out-of-town houses were constructed by the

wealthy, with many still surviving to this day. Within the city, large houses

were constructed in terraces, such as Colleton Crescent, Barnfield

Crescent etc. Other

properties were detached, or semi detached, as can be seen in Baring Crescent.

Other areas were to follow the

pattern, and out-of-town houses were constructed by the wealthy, with many

still surviving to this day. A good example can be found in the houses of

Topsham Road. Larkbeare, seen in Braun & Hogenberg (1618) and Izacke

(1677), was one of three properties known with this name. Great Larkbeare

and Little Larkbeare stood at the bottom of Holloway Street, at the

junction of today’s Robert’s Road. The modern Larkbeare still stands

next to St Leonard’s church. Mount Radford, was earlier known as Radford

Place (see Speed, 1610). In the 1700s, this house was occupied by the

Baring family, creators of Barings Bank. Adjacent to Mount Radford was

Parkerswell, seen in Hayman (1805). This house was probably constructed

a few years before, possibly at the end of the 18th century. Coaver was probably also built

at the end of the 18th century, or the early 19th century and is shown in Hayman’s maps of 1806

and 1828. Bellair, also seen in Hayman (1806 and 1828), was built in

1710 by wealthy grocer John Vowler. Both Coaver and Bellair,

together with their respective land, have in recent years been incorporated

into Devon County Hall, headquarters of the Devon County Council. Maps before

1900 do not extend much further than Bellair, but there are several

other properties in Topsham Road that were built by wealthy merchants, and

these include Otago, Buckerell Lodge, Wear House, Fairfield,

Abbeville, Feltrim etc.

Several local businessmen

became rich as a result of the “building boom” of the time, including

brickworks owner and property developer John Sampson, and builders William

Hooper and Matthew Nosworthy. Much of their work can still be seen in Heavitree, Polsloe,

Southernhay and other areas. Hooper, for example, was responsible for Higher

Summerlands (destroyed in the Exeter Blitz), Lower Summerlands, Baring Place, the elegant Chichester Place, and much of St. Leonard’s Road. Nosworthy is remembered for his properties in Barnfield

Crescent, Colleton Crescent and the original Dix’s Field (also destroyed in the Exeter Blitz). Sampson’s Lane, in

Polsloe, is named after John Sampson. Two of Exeter’s markets, the Higher

Market in Queen Street, and the Lower Market in Fore Street were built by Hooper, but designed by the respected

architect Charles Fowler, who was also responsible for the design of London’s Covent

Garden, and, more locally, the

gatehouse of Powderham Castle, home of the Earls of Devon. The Higher Market still exists,

but in its new role as a shopping mall.

Markets were of considerable importance to the city, being held on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, although later reduced to just Fridays. Fairs would be held on the third Wednesday of February, May and July, and the second Wednesday in December. The markets and fairs were for both for cattle and merchandise. The ancient Fair named Crollditch is now The Lammas Fair and is still acknowledged in the city.

Transport improves

Victorian

Exeter saw the arrival of the railway. Despite Besley including the line of the

South Devon Railway in his maps of 1836 and 1839 (20) and projecting a line to

cross Bonhay and Great Shilhay, the first trains did not arrive in Exeter until

1844, the line being officially opened on 1st May with a grand dinner being

held in the goods shed. And, of course, the Bristol and Exeter Railway Station

was built near the Red Cow Inn and the line crossed the river avoiding Bonhay

etc. as seen in Warren’s map, also executed for Besley (30). Within 20 years

Queen Street station was

constructed as the rival London & South Western Railway entered the city.

Its arrival was forecast on Featherstone’s small map circa 1858 (40). The

railway system throughout the country was fast increasing as business people

saw a much quicker and easier method of transporting their wares from one place

to another, and

passengers were able to reach their destinations far more quickly. A

journey from London, for which with the Telegraph post coach had taken

17 hours, could now be done in just four and a half on the express train. And

despite low wages, the average worker was able to afford a ride on the railway

on the increasing number of free days.

Wages

were comparatively low and hours were often long, with some workers toiling

from 6.00 am until 5.30 pm. In the mid

1800s, a labourer would be earning less than one pound a week, but more skilled

people were able to command from four pence to six pence an hour, and for a

fifty-six hour week they were able to earn almost two pounds. By the early

1900s, working hours reduced to around 48 per week and there were more public

holidays but pay rates remained fairly constant.

At

the same time, the Exeter Canal was seeing a

boom in trade, with ships bringing coal, timber, oil and other goods into the

city. On the Quayside, large

warehouses were constructed (still standing and well-used today) by businesses

who relied on shipping for bringing their goods to Exeter. Large iron foundries

were constructed in the lower part of the city, the Victorian era being renowned

for ornate ironwork in buildings and in the streets of the city. Three of

Exeter’s best-known foundries were Bodleys

(founded 1790), Willeys (founded 1860) and Garton & King, the latter being

able to boast of their beginnings in the mid 1600s!

The tramcar system of public

transport in Exeter started with horse drawn vehicles, but at the end of the 19th, electric

trams were in operation – powered by electricity running from the Rockfield

Works in New North Road. This is shown as “Electricity Station” in

Walker Boutall (1895) and Ward Lock (1898). In 1905 a new Power Station was

opened in Haven Road, and the Rockfield Works was sold. From 1905 until 1931

trams continued to be powered from Haven Road.

To

provide for this increase in transport needs, new roads had to be built and

some maps are still available which show the thoughts of those contemporary

city planners. Hackett’s maps, especially, indicate the road needs of the 1830s

and project the routes of the New North Devon Road past the barracks and the

New Road extending from Bedford Crescent out into the suburbs (see 21, 22 and Hackett

II ).

Exeter as a Meeting Place

Being such an important city, Exeter

was obviously the place for merchants, traders, and the general public to meet.

The ale-houses mentioned previously were, of course gathering places for all

and sundry. It is claimed that Sir Francis Drake took coffee in Mol’s Coffee

House, and ale in the Ship Inn in Martin’s Lane. The former claim is debatable.

John Dyer leased the building (previously the Anneuller’s College) from 1585

and some Armada negotiations took place there but it wasn’t really a coffee

house until about 1726 when it was advertised in Brice’s Weekly Journal.

A large room on the first floor is decorated with no less than forty-six coats

of arms of the more noted Devon families who presumably made Mol’s a rendezvous

when they visited Exeter. However, hotels and larger ale houses were frequently

used for meetings. Some two hundred members of the Devonshire Chamber of

Agriculture met at the Half Moon Hotel, in High Street four times a year. In

1850 they played host to the Royal Agricultural Show and two guides were

produced specially for the occasion (see 33 and 34).

The Exeter Literary Society,

established in 1841, met at their premises in Barnfield Road, now The Barnfield

Theatre. Here there were reading rooms in which the weekly lectures took place,

with smaller discussion groups using other rooms in the building. In 1850 the

Society had no less than 550 members. Maps will show earlier meeting places

such as Taylors Hall and James Meeting Place.

There were other meeting places of

perhaps more formal surroundings. The Devon and Exeter Institution, at No 7 The

Close, is a reading room and library for its members. The Institution was

founded in 1813 “for promoting Science

Literature and Art, and for illustrating the Natural and civil History of the

County of Devon and the city of Exeter” and remains in constant use today for meetings, lectures and

research.

The Victoria Hall in Queen Street,

no longer in existence, was built in 1869 to provide a room large enough to

accommodate two thousand people expected for the British Association Meeting

held in Exeter that year. There were also ancillary lecture rooms, committee

rooms and a sale room. It was also the venue for concerts, exhibitions, public

dinners and balls. During the Meeting it was used as the location for the

Geography section as well as for Inaugural and Other Addresses.

In 1894 Exeter was again host to a prestigious meeting when the Church Congress was held in October (61).

Changes in the City

Exeter’s

layout has, of course, changed dramatically since Roman days, although the

basic “enclosed” city can still be seen in aerial photographs, and much of the

Roman wall is still in place. Probably one of the most important changes was

that of the High Street/Fore Street link to the west. Hooker’s map of 1587

shows the High Street continuing down to the River Exe, but to the northern

side of the West Gate. The road that ran down directly to the West Gate was

Stepcote Hill – then the main exit route from the city centre. Nicholls has Strip

Coat Hill! Going out of the West Gate took the traveller across the bridge

crossing the Exe, and into St Thomas. Stepcote Hill today remains very much as

it was, but it must have been very difficult to traverse as it is steep and

cobbled - although William of Orange managed it (with 200 blacks from his

plantations) in 1688. The upper storeys of houses corbelled out and the first

floors on either side were extremely close. The layout is clearly shown in

Braun & Hogenberg’s map of 1618, and in Donn’s map of 1765. However, by the

late eighteenth century things had changed, and Tozer’s map of 1872 shows the

High Street leading down to Fore street, which in turn went down to the new

river crossing to the north of the West Gate. Stepcote Hill was now redundant as

a main exit.

Exe

Bridge was at one time a mere timber structure, replaced in the 1200s by a new

stone structure of seventeen arches, as can be seen in various maps of the 16th

and 17th centuries. In the latter part of the 18th century,

this bridge was also replaced, although several of the original arches can now

been seen between the plain and uninteresting 20th century

structures, Exe Bridge North and Exe Bridge South.

Rocque’s

map of 1764 shows a Workhouse situated a considerable distance from the City,

on the London Road. This was recently the site of the Royal Devon and Exeter

Hospital at Heavitree, although much of that (at the time of writing) is set to

be demolished for a supermarket! Tozer is interesting as he shows several

important changes. We now see the new Devon County Gaol, together with smaller

changes such as New Cut, which takes the pedestrian from Southernhay to the

Cathedral. Also depicted is the Theatre in Waterbeer Street, but although this

building was in being in the early 1700s, it is not shown as such prior to

Rocque. The building can be seen, though not named as a Theatre. In 1787 a new

Theatre was constructed at the junction of Southernhay and the new Bedford

Circus, and can be seen on Tozer’s map. This theatre was destroyed by fire in

1820, and was replaced by another in 1821. In 1885 that building was also

destroyed by fire, but never replaced. For some reason, Freeman’s map of 1887

and Cassell’s of 1888 both continue to show the theatre.

Perhaps

Bedford Circus deserves a special mention. No longer existing, thanks to the

bombing raids in 1942, Bedford Circus has a “special” place in Exeter’s recent

history. Originally the site of a Dominican Monastery, it later became Bedford

House, the family home of Lord John Russell, the Duke of Bedford. It was in

this house that Queen Henrietta Maria (wife of Charles I) gave birth to

Princess Henrietta, having stopped off at Exeter during the Civil War in

England, as she fled this country for homeland, France. The house was

demolished in 1783, to allow Bedford Circus to be constructed. Portman (1966)

states that the Circus was completed in 1825. It contained some of Exeter’s

finest Georgian houses, most of which were five storeys if their basements are

included. The properties were largely owned, or at least occupied, by

professional businessmen such as accountants, solicitors, architects etc. It

was severely damaged during 1942, and although one or two properties such as

Bedford Chapel could have been saved, the whole area was demolished and the new

Bedford Street laid out. Sadly the modern construction was nowhere near as

attractive as the original. Bedford Circus can be seen in various maps

including Hackett (23), where the Bedford Chapel is shown as a detached

building to the south of the Circus – although not named as such.

Brown/Schmollinger 1835 and later maps do name it.

A myriad

of changes took place during the late 1700s, and early 1800s, but far too many

to individually mention here. Major developments included the extension to the

port. In Hayman’s map of 1828 we see the “proposed Basin” – an important

feature of Exeter to this day – for it stands at the end of the Exeter Ship

Canal, the only way that ships can now reach the City (see above). One of the

next important changes was the introduction of a new road from the High Street

towards the new projected railway station at St David’s. This road was built in

1834, and was named Higher Market Street until some years later, when it was

re-named Queen Street to honour the then monarch, Queen Victoria. The first map

to show this street appears to be that of Brown and Schmollinger in 1835. It is

interesting to note that on this same map, the gates of the City are no longer

shown, as the last gate to be demolished was the North Gate, in 1834.

The name

Besley is probably more associated with Street Directories, but of course many

of the directories included maps. The first map of Exeter specifically

commissioned for Besley (by Warren in 1845) is interesting in that it depicts

the new railway system running along the west side of the city. By this time,

considerable areas of land outside the city walls had now been developed for

housing. This map when compared with maps of the 1700s, for example, shows how

this development evolved. Warren’s map also clearly shows the two Markets,

Higher (Queen Street) and Lower (Market Street), both constructed in the 1830s

to the design of Charles Fowler.

Oliver’s

reproduction of Norden’s plan of the Castle, which later became a court house,

is of particular interest today because from 2004 the castle ceased to be used

for Court and civic purposes, and became the property of a developer who

planned great things – including a restaurant and apartments that, in 2010,

have only partially come to fruition. Early maps (e.g. Tozer) depict the small

Chapel of St Mary that once stood just inside the Norman gatehouse, but the

chapel was demolished in the late 18th century. It was later

replaced with the Castle Keeper’s cottage, which is shown on later maps, but

can be confused with the original chapel.

From 1850

it is impossible to list the changes that have taken place in the City, but

many of these changes can be seen on the

maps of the late 1800s and early 1900s when one looks carefully. This was the

period when many roads, streets and crescents were created in the city. Since

then the City has seen constant change, with huge areas of housing and general

development.

Exeter in the 1939-45 War

The most significant changes to the City in modern times took place during the 1941/1942 bombing raids on Exeter during the Second World War.

Although

the events of the 1939-1945 war are outside the scope of this present volume

and have been discussed in full in other publications it is, perhaps, important

to mention how it changed the face of

Exeter. In 1942 Exeter received a series of bombing raids by the German

Luftwaffe. Exeter was of little importance to the Germans and was probably

simply unlucky to become a target. Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, then in

charge of Bomber Command, had wanted to experiment on bringing in waves of

aircraft instead of a single squadron and ordered experimental raids to be

carried out on Lübeck, a small, attractive town on the Baltic shores of

Germany. Lübeck was of little significance, apart from its location close to a

German submarine base. The raids on Lübeck left the town a smouldering ruin,

causing Hitler to order attacks on English towns and cities that were, like

Lübeck, historic and of great beauty. However, Exeter did have a fighter station responsible for the airspace west of Portland. It is popular

belief that targets were chosen from the Baedeker

Guide Books, the German equivalents of the Murray or A & C Black guides

of Great Britain.

During

the raids on Exeter - which became known as Baedaker

or reprisal raids - much of the city’s historic centre was devastated,

with many fine buildings lost. Especially hard hit was the area where the High

Street and Bedford Street join and some of the buildings to be destroyed

included Deller’s Café at the corner, a splendid building on three storeys and

not just a café, but an important meeting place for all and sundry. Other

buildings destroyed included the delightful Bampfylde House, which although

internally ravaged by fire, was capable of being restored but was demolished,

and the Hall of the Vicars Choral, the home for several vicars attached to the

Cathedral. The gas works at Haven Bank, shown on many pre-1900 maps, was bombed

but suffered the loss of only one tank but the Lower Market was caught in the

blazes around South Street, Market Street, Coombe Street and Fore Street and

was lost. The city library in Castle Street was taken over as a control centre,

but was largely destroyed by fire and had to be evacuated. The lovely Bedford

Circus, its development plotted so carefully in the 19th century maps, was

destroyed and demolished. The Lower Market was largely destroyed

in the Exeter Blitz, but the

granite shell remained and could have been restored, but was, sadly,

demolished.

Since WWII Exeter has become a much

larger city, if not as beautiful as it was. In more recent years, Exeter has

taken in outlying suburbs, such as Alphington and, Pinhoe and now has some

125,000 residents, and is a thriving, bustling community. Yet it has changed

dramatically, possibly for the worse in many respects. In his book W.G. Hoskins

(1960) regretted that Exeter was no longer a city of culture. There was, he

said, a profound difference between modern Exeter and that of one hundred years

ago. That, of course, is due to progress and modernisation, but Hoskins is

right in saying that the culture of Exeter – and probably many similar cities

– has changed. So has the architecture, so has the size and

layout. Indeed, so has the population itself changed, for we all now live in a

modern society that reflects little on the life of centuries past. Was Exeter a

better place in medieval times, or was The Georgian era better? Did the

Victorians live a better, more cultured life, or are we now living in better

times? Perhaps it is better for the reader to decide.

Despite all the change, despite the

intrusion of past invaders, despite the devastation caused by the last War, and

despite modern challenges, Exeter is still a delightful place in which to live

and work.[2]

Return to Introduction

Go to Catalogue of Maps

[1]

After 1688 woollen products were allowed to be exported free of duty and Exeter

became a major trading centre for both export and import as well as re-export.

Land transport was expensive and difficult and the coastal trade expanded

throughout the 18th century, and with the trade both canal and quay grew in

importance. The wool trade had two high points: in 1710 the value of the export

of serge to Holland was £386,000 (compared to Norwich at £239,000 and London

only £20,000); after a period of decline, the serge trade was worth roughly

£600,000 in 1777. The collapse that followed was effected first by the American

War of Independence and then by

the French revolutionary wars. By 1820 the port was only engaged in coastal

traffic and by 1820 the woollen trade was almost irrelevant in the city.

Vancouver (B&B 70, 1808) placed the collapse much earlier, stating that

exports in 1800 were worth only £24,000!

[2] I

would like to acknowledge the help of both Andrew Passmore B.Sc. and David

Cornforth.

No comments:

Post a Comment